Regional Art Workshop Instructors in Illinois Wisconsin and Iowa

| Hawkeye and palette design regarded equally the logo of the Federal Art Projection | |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | 29 August 1935 (1935-08-29) |

| Dissolved | 1943 (1943) |

| Jurisdiction | The states |

| Headquarters | Washington, D.C. |

| Agency executive |

|

| Parent department | Works Progress Assistants (WPA) |

The Federal Fine art Project (1935–1943) was a New Deal plan to fund the visual arts in the U.s.. Under national managing director Holger Cahill, it was 1 of five Federal Projection Number One projects sponsored by the Works Progress Administration (WPA), and the largest of the New Bargain fine art projects. It was created not as a cultural activity, but as a relief mensurate to employ artists and artisans to create murals, easel paintings, sculpture, graphic fine art, posters, photography, theatre scenic design, and craft. The WPA Federal Art Project established more 100 community art centers throughout the state, researched and documented American design, commissioned a pregnant body of public art without restriction to content or subject matter, and sustained some ten,000 artists and craft workers during the Bang-up Low.

Background [edit]

Affiche summarizing Federal Art Project employment and activities (November ane, 1936)

The Federal Art Projection was the visual arts arm of the Great Depression-era WPA, a Federal 1 program. Funded under the Emergency Relief Cribbing Act of 1935, information technology operated from August 29, 1935, until June 30, 1943. It was created equally a relief measure to use artists and artisans to create murals, easel paintings, sculpture, graphic fine art, posters, photographs, Index of American Design documentation, museum and theatre scenic design, and arts and crafts. The Federal Fine art Project operated community fine art centers throughout the country where arts and crafts workers and artists worked, exhibited, and educated others.[2] The project created more than than 200,000 separate works, some of them remaining among the most significant pieces of public art in the state.[3]

The Federal Art Project'southward primary goals were to apply out-of-work artists and to provide art for nonfederal municipal buildings and public spaces. Artists were paid $23.threescore a calendar week; tax-supported institutions such every bit schools, hospitals, and public buildings paid simply for materials.[4] The work was divided into art production, art instruction, and art research. The primary output of the fine art-research group was the Index of American Pattern, a mammoth and comprehensive written report of American material culture.

As many every bit 10,000 artists were commissioned to produce work for the WPA Federal Art Project,[five] the largest of the New Deal art projects. Iii comparable but distinctly separate New Deal fine art projects were administered by the The states Department of the Treasury: the Public Works of Fine art Projection (1933–1934), the Section of Painting and Sculpture (1934–1943), and the Treasury Relief Art Project (1935–1938).[6]

The WPA plan made no stardom between representational and nonrepresentational fine art. Abstraction had not all the same gained favor in the 1930s and 1940s, and then was virtually unsalable. Equally a result, the Federal Art Project supported such iconic artists as Jackson Pollock earlier their piece of work could earn them income.[seven]

I particular success was the Milwaukee Handicraft Projection, which started in 1935 equally an experiment that employed 900 people who were classified as unemployable due to their age or disability.[1] : 164 The projection came to employ about 5,000 unskilled workers, many of them women and the long-term unemployed. Historian John Gurda observed that the city'south unemployment hovered at 40% in 1933. "In that yr," he said, "53 per centum of Milwaukee'south property taxes went unpaid considering people just could not afford to make the taxation payments."[viii] Workers were taught bookbinding, cake printing, and design, which they used to create handmade art books and children's books. They produced toys, dolls,[9] theatre costumes, quilts,[8] rugs, draperies, wall hangings, and piece of furniture that were purchased by schools, hospitals,[1] : 164 and municipal organizations[x] for the cost of materials only.[11] In 2014, when the Museum of Wisconsin Art mounted an exhibition of items created by the Milwaukee Handicraft Projection, piece of furniture from it was yet beingness used at the Milwaukee Public Library.[eight]

Holger Cahill was national manager of the Federal Fine art Project. Other administrators included Audrey McMahon, director of the New York Region (New York, New Jersey, and Philadelphia); Clement B. Haupers, director for Minnesota;[12] George Godfrey Thorp (Illinois), [13] and Robert Bruce Inverarity, director for Washington. Regional New York supervisors of the Federal Art Project have included sculptor William Ehrich (1897–1960) of the Buffalo Unit (1938–1939), project director of the Buffalo Zoo expansion.[fourteen]

Notable artists [edit]

Some 10,000 artists were commissioned to work for the Federal Fine art Project.[5] Notable artists include the following:

- William Abbenseth[15]

- Berenice Abbott[sixteen]

- Ida York Abelman[1] : 178

- Gertrude Abercrombie[17]

- Benjamin Abramowitz[eighteen]

- Abe Ajay[19]

- Ivan Albright[one] : 161

- Maxine Albro[twenty]

- Charles Alston[21]

- Harold Ambellan[22]

- Luis Arenal[23]

- Bruce Ariss[24]

- Victor Arnautoff[25]

- Sheva Ausubel[26]

- Jozef Bakos[27]

- Henry Bannarn[28]

- Belle Baranceanu[29]

- Patrociño Barela[xxx]

- Volition Barnet[31]

- Richmond Barthé[32]

- Herbert Bayer[1] : 195

- William Baziotes[33]

- Lester Beall[1] : 194

- Harrison Begay[34]

- Daisy Maud Bellis[35] [36]

- Rainey Bennett[37] : 138

- Aaron Berkman[38]

- Leon Bibel[39]

- Robert Blackburn[1] : 170

- Arnold Blanch[37] : 153

- Lucile Blanch[40]

- Lucienne Bloch[4]

- Aaron Bohrod[37] : 144

- Ilya Bolotowsky[41] [42]

- Adele Brandeis[43]

- Louise Brann[44]

- Edgar Britton[37] : 138

- Manuel Bromberg[45]

- James Brooks[46] [47]

- Selma Burke[48]

- Letterio Calapai[49]

- Samuel Cashwan[37] : 156

- Giorgio Cavallon[50]

- Daniel Celentano[51]

- Dane Chanase[52]

- Fay Chong[53]

- Claude Clark[54]

- Max Arthur Cohn[55]

- Eldzier Cortor[56]

- Arthur Covey[57]

- Alfred D. Crimi[58]

- Francis Criss[59]

- Allan Crite[37] : 144

- Robert Cronbach[22]

- John Steuart Back-scratch[57]

- Philip Campbell Curtis[60]

- James Daugherty[57]

- Stuart Davis[61]

- Adolf Dehn[62]

- Willem de Kooning[1] : 186

- Burgoyne Diller[63]

- Isami Doi[64]

- Mabel Dwight[1] : 180, 182

- Ruth Egri[65]

- Fritz Eichenberg[66]

- Jacob Elshin[53]

- George Pearse Ennis[67]

- Angna Enters[68]

- Philip Evergood[1] : 161, 174

- Louis Ferstadt[69]

- Alexander Finta[70]

- Joseph Chip[34]

- Seymour Fogel[4] [37] : 138

- Lily Furedi[71]

- Todros Geller[72]

- Aaron Gelman[57]

- Eugenie Gershoy[73]

- Enrico Glicenstein[74]

- Vincent Glinsky[75]

- Bertram Goodman[76]

- Arshile Gorky[1] : 186

- Harry Gottlieb[37] : 154

- Blanche Grambs[37] : 154

- Morris Graves[53]

- Balcomb Greene[42]

- Marion Greenwood[77]

- Waylande Gregory[78]

- Philip Guston[1] : 161

- Irving Guyer[79]

- Abraham Harriton[80]

- Marsden Hartley[1] : 161

- Knute Heldner[81]

- Baronial Henkel[82]

- Ralf Henricksen[83]

- Magnus Colcord Heurlin[57]

- Hilaire Hiler[37] : 145

- Louis Hirshman[84] [85]

- Donal Hord[86]

- Axel Horn[87]

- Milton Horn[88]

- Allan Houser[34]

- Eitaro Ishigaki[89]

- Edwin Boyd Johnson[37] : 140

- Sargent Claude Johnson[ninety]

- Tom Loftin Johnson[91]

- William H. Johnson[92]

- Leonard D. Jungwirth[56]

- Reuben Kadish[93]

- Sheffield Kagy[94]

- Jacob Kainen[95]

- David Karfunkle[96]

- Leon Kelly[37] : 145

- Paul Kelpe[42]

- Troy Kinney[57]

- Georgina Klitgaard[37] : 145

- Gene Kloss[37] : 154

- Karl Knaths[37] : 141, 146

- Edwin B. Knutesen[97]

- Lee Krasner[98]

- Kalman Kubinyi[99]

- Yasuo Kuniyoshi[37] : 154

- Jacob Lawrence[i] : 161

- Edward Laning[37] : 141

- Michael Lantz[100]

- Blanche Lazzell[37] : 154

- Tom Lea[101]

- Lawrence Lebduska[37] : 146

- Joseph LeBoit[102]

- William Robinson Leigh[34]

- Julian Eastward. Levi[37] : 146

- Jack Levine[37] : 146

- Monty Lewis[103]

- Elba Lightfoot[104]

- Abraham Lishinsky[37] : 141

- Michael Loew[105]

- Thomas Gaetano LoMedico[106]

- Louis Lozowick[1] : 168, 171

- Nan Lurie[37] : 155

- Guy Maccoy[107]

- Stanton Macdonald-Wright[108]

- George McNeil[37] : 144

- Moissaye Marans[109]

- David Margolis[110]

- Kyra Markham[37] : 155

- Jack Markow][111]

- Mercedes Matter[112]

- Jan Matulka[37] : 144

- Dina Melicov[113]

- Hugh Mesibov[114]

- Katherine Milhous[37] : 163

- Jo Mora[115]

- Helmuth Naumer[34]

- Louise Nevelson[116]

- James Michael Newell[117]

- Spencer Baird Nichols[57]

- Elizabeth Olds[118]

- John Opper[119]

- William C. Palmer[37] : 142 [120]

- Phillip Pavia[57]

- Irene Rice Pereira[121]

- Jackson Pollock[122]

- George Mail[37] : 150

- Gregorio Prestopino[37] : 147

- Mac Raboy[123]

- Anton Refregier[37] : 155

- Ad Reinhardt[124]

- Misha Reznikoff[37] : 147

- Mischa Richter[57]

- Diego Rivera[125]

- José de Rivera[126]

- Emanuel Glicen Romano[127]

- Marking Rothko[1] : 161

- Alexander Rummler[57]

- Augusta Savage[128] [129]

- Concetta Scaravaglione[37] : 157

- Louis Schanker[130]

- Edwin Scheier[131]

- Mary Scheier[131]

- Carl Schmitt[57]

- William S. Schwartz[37] : 147

- Georgette Seabrooke[132]

- Ben Shahn[133] [134]

- William Howard Shuster[135]

- Mitchell Siporin[136]

- John French Sloan[5]

- Joseph Solman[137]

- William Sommer[37] : 151

- Isaac Soyer[138]

- Moses Soyer[one] : 161

- Raphael Soyer[1] : 32

- Ralph Stackpole[139]

- Cesare Stea[140]

- Walter Steinhart[57]

- Joseph Stella[ane] : 175

- Harry Sternberg[1] : 167

- Sakari Suzuki[141]

- Albert Swinden[42] [142]

- Rufino Tamayo[37] : 151

- Elizabeth Terrell[37] : 147

- Lenore Thomas[i] : 323

- Dox Thrash[3] : 373

- Marker Tobey[i] : 161 [53]

- Harry Everett Townsend[57]

- Edward Buk Ulreich[47]

- Charles Umlauf[143]

- Jacques Van Aalten[144]

- Stuyvesant Van Veen[145]

- Herman Volz[146]

- Mark Voris[147]

- John Augustus Walker[148]

- Andrew Winter[five]

- Jean Xceron[149]

- Edgar Yaeger[150]

- Bernard Zakheim[151] [152]

- Karl Zerbe[37] : 148

[edit]

Jacksonville Negro Art Center, Jacksonville, Florida

Poster for the opening of the Stonemason City Art Middle, Mason Urban center, Iowa (1941)

Course at the Harlem Customs Fine art Middle (Jan ane, 1938)

Poster for the open up business firm of the Greensboro Art Center, Greensboro, North Carolina (1937)

Curry County Art Middle, Gold Beach, Oregon

The showtime federally sponsored customs art center opened in December 1936 in Raleigh, Due north Carolina.[153]

| Land | City | Name | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | Birmingham | Extension art gallery[iii] : 441 | |

| Alabama | Birmingham | Healey Schoolhouse Art Gallery | [3] : 441 |

| Alabama | Mobile | Mobile Art Centre, Public Library Edifice | [3] : 441 |

| Arizona | Phoenix | Phoenix Art Center | [3] : 441 |

| District of Columbia | Washington, D.C. | Children'south Art Gallery | [iii] : 441 |

| Florida | Bradenton | Bradenton Art Center | [three] : 441 |

| Florida | Coral Gables | Coral Gables Art Gallery | Extension art gallery[3] : 441 |

| Florida | Daytona Beach | Daytona Beach Fine art Middle | [3] : 441 |

| Florida | Jacksonville | Jacksonville Art Eye | [3] : 441 |

| Florida | Jacksonville | Jacksonville Embankment Fine art Gallery | Extension art gallery[3] : 441 |

| Florida | Jacksonville | Jacksonville Negro Art Center | Extension art gallery[3] : 441 [154] |

| Florida | Key West | Key West Customs Fine art Center | [3] : 441 |

| Florida | Miami | Miami Fine art Center | [3] : 441 |

| Florida | Milton | Milton Art Gallery | Extension art gallery[3] : 441 |

| Florida | New Smyrna Beach | New Smyrna Beach Art Center | [3] : 441 |

| Florida | Ocala | Ocala Fine art Center | [iii] : 441 |

| Florida | Pensacola | Pensacola Art Eye | [3] : 441 |

| Florida | St. Petersburg | Hashemite kingdom of jordan Park Negro Exhibition Eye | [3] : 441 |

| Florida | Leningrad | St. petersburg Art Middle | [3] : 442 |

| Florida | St. Petersburg | Saint petersburg Civic Exhibition Center | [3] : 442 |

| Florida | Tampa | Tampa Art Center | [3] : 442 |

| Florida | Tampa | West Tampa Negro Fine art Gallery | [3] : 442 |

| Illinois | Chicago | Hyde Park Art Middle | [3] : 442 |

| Illinois | Chicago | South Side Community Art Center | [3] : 442 |

| Iowa | Mason City | Mason City Fine art Middle | [3] : 442 |

| Iowa | Ottumwa | Ottumwa Art Center | [iii] : 442 |

| Iowa | Sioux Urban center | Sioux Metropolis Art Heart | [3] : 442 |

| Kansas | Topeka | Topeka Art Heart | [iii] : 442 |

| Minnesota | Minneapolis | Walker Fine art Center | [iii] : 442 [155] |

| Mississippi | Greenville | Delta Art Center | [three] : 442 |

| Mississippi | Oxford | Oxford Fine art Center | [3] : 442 [156] |

| Mississippi | Sunflower | Sunflower Canton Art Center | [3] : 442 |

| Missouri | St. Louis | The People's Art Center | [3] : 442 |

| Montana | Butte | Butte Art Center | [iii] : 442 |

| Montana | Cracking Falls | Bully Falls Art Eye | [3] : 442 |

| New Mexico | Gallup | Gallup Fine art Middle | [iii] : 443 [34] |

| New Mexico | Melrose | Melrose Art Center | [3] : 443 |

| New Mexico | Roswell | Roswell Museum and Fine art Middle | [three] : 443 |

| New York Metropolis | Brooklyn | Brooklyn Community Art Center | [3] : 443 |

| New York City | Manhattan | Contemporary Fine art Center | [3] : 443 [157] |

| New York City | Harlem | Harlem Customs Art Center | [3] : 443 |

| New York Metropolis | Flushing, Queens | Queensboro Community Art Center | [3] : 443 |

| North Carolina | Cary | Cary Gallery | Extension fine art gallery[iii] : 443 |

| Northward Carolina | Greensboro | Greensboro Art Centre | [153] |

| North Carolina | Greenville | Greenville Fine art Gallery | [3] : 443 |

| Due north Carolina | Raleigh | Crosby-Garfield Schoolhouse | Extension art gallery[three] : 443 |

| North Carolina | Raleigh | Needham B. Broughton High School | Extension art gallery[3] : 443 |

| North Carolina | Raleigh | Raleigh Art Center | [3] : 444 |

| Northward Carolina | Wilmington | Wilmington Art Center | [3] : 443 |

| Oklahoma | Bristow | Bristow Art Gallery | Extension art gallery[3] : 443 |

| Oklahoma | Claremore | Claremore Fine art Gallery | Extension fine art gallery[three] : 443 |

| Oklahoma | Claremore | Will Rogers Public Library | Extension art gallery[3] : 443 |

| Oklahoma | Clinton | Clinton Art Gallery | Extension art gallery[3] : 443 |

| Oklahoma | Cushing | Cushing Fine art Gallery | Extension art gallery[3] : 443 |

| Oklahoma | Edmond | Edmond Art Gallery | Extension art gallery[iii] : 443 |

| Oklahoma | Marlow | Marlow Art Gallery | Extension art gallery[3] : 443 |

| Oklahoma | Oklahoma City | Oklahoma Art Eye | [3] : 443 |

| Oklahoma | Okmulgee | Okmulgee Art Center | Extension fine art gallery[3] : 443 |

| Oklahoma | Sapulpa | Sapulpa Art Gallery | Extension art gallery[3] : 443 |

| Oklahoma | Shawnee | Shawnee Art Gallery | Extension art gallery[3] : 443 |

| Oklahoma | Skiatook | Skiatook Art Gallery | Extension fine art gallery[iii] : 443 |

| Oregon | Gold Beach | Curry Canton Art Center | [3] : 444 |

| Oregon | La Grande | Grande Ronde Valley Art Eye | [iii] : 444 |

| Oregon | Salem | Salem Art Eye | [three] : 444 |

| Pennsylvania | Somerset | Somerset Art Middle | [3] : 444 |

| Tennessee | Chattanooga | Hamilton County Fine art Eye | [iii] : 444 |

| Tennessee | Memphis | LeMoyne Art Eye | [three] : 444 |

| Tennessee | Nashville | Peabody Art Heart | [3] : 444 |

| Tennessee | Norris | Anderson County Art Center | [iii] : 444 |

| Utah | Cedar City | Cedar City Art Exhibition Clan | Extension art gallery[three] : 444 |

| Utah | Helper | Helper Community Gallery | Extension art gallery[3] : 444 |

| Utah | Toll | Price Community Gallery | Extension art gallery[3] : 444 |

| Utah | Provo | Provo Community Gallery | Extension fine art gallery[3] : 444 |

| Utah | Common salt Lake City | Utah State Fine art Heart | [3] : 444 |

| Virginia | Altavista | Altavista Extension Gallery | Extension art gallery[3] : 445 |

| Virginia | Big Stone Gap | Large Stone Gap Fine art Gallery | [3] : 444 |

| Virginia | Lynchburg | Lynchburg Art Gallery | [3] : 444 |

| Virginia | Richmond | Children's Art Gallery | [3] : 444 |

| Virginia | Saluda | Middlesex County Museum | Extension art gallery[3] : 444 |

| Washington | Chehalis | Lewis County Exhibition Center | Extension fine art gallery[three] : 444 |

| Washington | Pullman | Washington Land College | Extension art gallery[iii] : 444 |

| Washington | Spokane | Spokane Art Centre | [3] : 444 [158] |

| Due west Virginia | Morgantown | Morgantown Fine art Center | [3] : 445 |

| Due west Virginia | Parkersburg | Parkersburg Art Eye | [iii] : 445 |

| West Virginia | Scotts Run | Scotts Run Fine art Gallery | Extension art gallery[3] : 445 |

| Wyoming | Casper | Casper Art Gallery | Extension art gallery[3] : 445 |

| Wyoming | Lander | Lander Art Gallery | Extension fine art gallery[iii] : 445 |

| Wyoming | Laramie | Laramie Art Heart | [3] : 445 |

| Wyoming | Newcastle | Lander Art Gallery | Extension art gallery[3] : 445 |

| Wyoming | Rawlins | Rawlins Fine art Gallery | Extension art gallery[3] : 445 |

| Wyoming | Riverton | Riverton Art Gallery | Extension fine art gallery[3] : 445 |

| Wyoming | Stone Springs | Stone Springs Fine art Gallery | Extension art gallery[3] : 445 |

| Wyoming | Sheridan | Sheridan Art Gallery | Extension art gallery[3] : 445 |

| Wyoming | Torrington | Torrington Art Gallery | Extension art gallery[3] : 445 |

Index of American Design [edit]

Federal Art Projection Illinois affiche for an exhibition of the Index of American Design

Every bit we study the drawings of the Index of American Design we realize that the hands that made the first ii hundred years of this country's material culture expressed something more than than untutored creative instinct and the rude vigor of a frontier civilization. … The Index, in bringing together thousands of particulars from various sections of the state, tells the story of American hand skills and traces intelligible patterns within that story.

—Holger Cahill, national director of the Federal Art Project[159] : xv

The Alphabetize of American Blueprint program of the Federal Art Project produced a pictorial survey of the crafts and decorative arts of the United States from the early colonial period to 1900. Artists working for the Index produced nearly eighteen,000 meticulously faithful watercolor drawings,[1] : 226 documenting material civilization by largely anonymous artisans.[159] : nine Objects range from piece of furniture, silver, drinking glass, stoneware and textiles to tavern signs, ships's figureheads, cigar-store figures, carousel horses, toys, tools and weather vanes.[i] : 224 [160] Photography was used only to a express degree since artists could more accurately and effectively present the form, character, color and texture of the objects. The all-time drawings approach the work of such 19th-century trompe-l'œil painters as William Harnett; bottom works correspond the process of artists who were given employment and practiced grooming.[159] : xiv

"It was non a nostalgic or antiquarian enterprise," wrote historian Roger G. Kennedy. "It was initiated by modernists dedicated to abstract design, hoping to influence industrial design — thus in many ways it parallelled the founding philosophy of the Museum of Modern Art in New York."[1] : 224

Like all WPA programs, the Index had the master purpose of providing employment.[161] Its part was to identify and record material of historical significance that had not been studied and was in danger of being lost. Its aim was to assemble together these pictorial records into a body of cloth that would form the basis for organic development of American design — a usable American past accessible to artists, designers, manufacturers, museums, libraries and schools. The United states had no single comprehensive collection of authenticated historical native design comparable to those available to scholars, artists and industrial designers in Europe.[162]

"In one sense the Index is a kind of archaeology," wrote Holger Cahill. "It helps to correct a bias which has tended to relegate the work of the craftsman and the folk artist to the hidden of our history where it can be recovered only by earthworks. In the past we have lost whole sequences out of their story, and accept all but forgotten the unique contribution of paw skills in our culture."[159] : xv

The Index of American Design operated in 34 states and the District of Columbia from 1935 to 1942. Information technology was founded by Romana Javitz, head of the Picture Drove of the New York Public Library, and material designer Ruth Reeves.[1] : 224 Reeves was appointed the beginning national coordinator; she was succeeded by C. Adolph Glassgold (1936) and Benjamin Knotts (1940). Constance Rourke was national editor.[159] : xii The piece of work is in the collection of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.[163]

The Alphabetize employed an boilerplate of 300 artists during its vi years in operation.[159] : fourteen I artist was Magnus South. Fossum, a longtime farmer who was compelled by the Depression to motion from the Midwest to Florida. Later he lost his left paw in an accident in 1934, he produced watercolor renderings for the Index, using magnifiers and drafting instruments for accuracy and precision. Fossum eventually received an insurance settlement that fabricated it possible for him to buy another subcontract and exit the Federal Art Project.[1] : 228

In her essay,'Picturing a Usable Past,' Virginia Tuttle Clayton, curator of the 2002-2003 exhibition, Drawing on America'due south Past: Folk Art, Modernism, and the Index of American Pattern, held at the National Gallery of Art noted that "the Index of American Design was the result of an ambitious and artistic effort to furnish for the visual arts a usable past."[164]

-

church of sanctuario at chimayo-panel from reredos

-

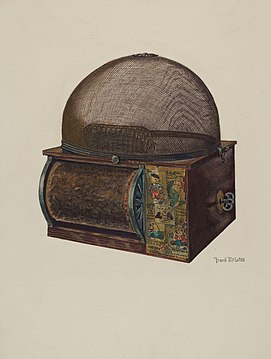

Fly Catcher, 1937.Frank McEntee - National Gallery of Art.

-

Magnus Fossum copying the 1770 Boston Town Coverlet (February 1940)

-

Boston Town Coverlet

Magnus Fossum (1935–1942) -

Poke Bonnet,Irene Lawson. Alphabetize of American Design.National Gallery of Art

-

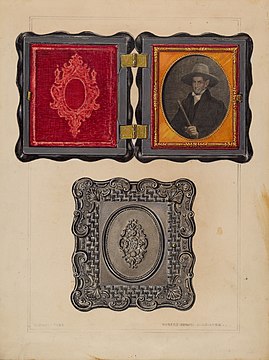

Daguerreotype Case Alphabetize of American Design

-

"Historic period of Knightly" Circus Wagon, c. 1938

-

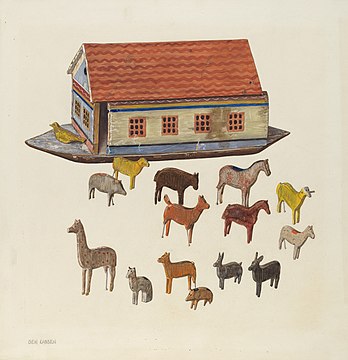

Noah'southward Ark with animals-Dominicus toy

WPA Art Recovery Project [edit]

| External video | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

Hundreds of thousands of artworks were commissioned under the Federal Art Project.[5] Many of the portable works have been lost, abased, or given away every bit unauthorized gifts. As custodian of the work, which remains federal property, the Full general Services Administration (GSA) maintains an inventory[166] and works with the FBI and art customs to identify and recover WPA art.[167] In 2010, it produced a 22-minute documentary about the WPA Art Recovery Project, "Returning America'south Art to America", narrated past Charles Osgood.[168]

In July 2014, the GSA estimated that only xx,000 of the portable works have been located to date.[166] [169] In 2015, GSA investigators plant 122 Federal Fine art Project paintings in California libraries, where about had been stored and forgotten.[170]

See also [edit]

- Listing of Federal Art Project artists

- Section of Painting and Sculpture

- Public Works of Art Projection

- Subcontract Security Administration which employed photographers.

References [edit]

- ^ a b c d eastward f g h i j thousand l one thousand n o p q r s t u v westward x y z aa ab Kennedy, Roger G.; Larkin, David (2009). When Art Worked: The New Deal, Fine art, and Democracy. New York: Rizzoli International Publications, Inc. ISBN978-0-8478-3089-iii.

- ^ "Employment and Activities poster for the WPA's Federal Art Project, 1936". Athenaeum of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-16 .

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k 50 g north o p q r s t u v w ten y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd exist bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm bn bo bp bq br bs bt bu bv bw bx past bz ca cb cc cd ce cf cg ch ci cj ck cl cm cn co cp cq Kalfatovic, Martin R. (1994). The New Deal Fine Arts Projects: A Bibliography, 1933–1992. Metuchen, Due north.J.: Scarecrow Press. ISBN0-8108-2749-2 . Retrieved 2015-06-17 .

- ^ a b c Brenner, Anita (April x, 1938). "America Creates American Murals". The New York Times . Retrieved 2015-06-sixteen .

- ^ a b c d due east Naylor, Brian (April 16, 2014). "New Deal Treasure: Government Searches For Long-Lost Art". All Things Considered. NPR. Retrieved 2015-06-thirteen .

- ^ "New Deal Artwork: GSA'south Inventory Project". General Services Administration. Retrieved 2015-06-16 .

- ^ Atkins, Robert (1993). ArtSpoke: A Guide to Modern Ideas, Movements, and Buzzwords, 1848-1944. Abbeville Press. ISBN 978-one-55859-388-vi.

- ^ a b c Whaley, M. P. (April 30, 2014). "Depression-Era Milwaukee Handicraft Project Put Thousands of People to Work". The Kathleen Dunn Show. Wisconsin Public Radio. Retrieved 2015-11-29 .

- ^ "WPA – Milwaukee Handicraft Projection". Museum of Wisconsin Art. Retrieved 2015-11-29 .

- ^ Roosevelt, Eleanor (November 13, 1936). "My Day". Eleanor Roosevelt Papers Project. The George Washington University. Retrieved 2015-06-sixteen .

- ^ "WPA Milwaukee Handicraft Project". School of Standing Pedagogy, Employment and Training Institute. University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee. Retrieved 2015-11-29 .

- ^ "WPA Art Project". Library. Minnesota Historical Society. Retrieved 2015-xi-29 .

- ^ Smithsonian. Athenaeum of American Fine art. George Godfrey Thorp papers, 1941–1970

- ^ Ehrich, Nancy and Roger. "William Ernst Ehrich Biography". Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- ^ "Oral history interview with William Abbenseth". Archives of American Fine art. Smithsonian Institution. November 23, 1964. Retrieved 2015-06-16 .

- ^ "Background". Changing New York. New York Public Library. Retrieved 2015-06-16 .

- ^ "Gertrude Abercrombie papers". Athenaeum of American Fine art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-eleven .

- ^ "The Creative person and His Life". The Artwork of Benjamin Abramowitz (1917–2011). S.A. Rosenbaum & Associates. Archived from the original on 2015-08-12. Retrieved 2015-06-sixteen .

- ^ "Abe Ajay, Industry". The Collection Online. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2015-06-22 .

- ^ "Oral history interview with Maxine Albro and Parker Hall". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Establishment. July 27, 1964. Retrieved 2015-06-sixteen .

- ^ "Oral history interview with Charles Henry Alston". Athenaeum of American Art. Smithsonian Establishment. September 28, 1965. Retrieved 2015-06-16 .

- ^ a b "The Artists of Buffalo's Willert Park Courts Sculptures". Western New York Heritage Press. Archived from the original on 2010-12-03. Retrieved 2015-06-15 .

- ^ "Luis Arenal". Athenaeum of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. August seven, 1936. Retrieved 2015-06-13 .

- ^ "Pacific Grove High School Landscape – Pacific Grove CA". The Living New Bargain. Department of Geography, University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 2015-06-15 .

- ^ "George Washington High School: Arnautoff Landscape – San Francisco CA". The Living New Bargain. Section of Geography, University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 2015-06-15 .

- ^ "Sheva Ausubel". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. March xxx, 1937. Retrieved 2015-06-13 .

- ^ "Oral history interview with Jozef and Teresa Bakos, 1965". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2016-04-20 .

- ^ "Henry W. Bannarn, ca. 1937". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Establishment. Retrieved 2015-06-17 .

- ^ "Belle Baranceanu (1902-1988)". San Diego History Center. Retrieved 2016-04-xx .

- ^ "Oral history interview with Patrociño Barela". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. July 2, 1964. Retrieved 2015-06-15 .

- ^ "Volition Barnet, Labor". The Collection Online. Metropolitan Museum of Fine art. Retrieved 2015-06-22 .

- ^ "Richmond Barthe, 1941 Apr. four". Archives of American Fine art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17 .

- ^ "William and Ethel Baziotes papers, 1916–1992". Archives of American Fine art. Smithsonian Establishment. Retrieved 2015-06-22 .

- ^ a b c d e f "WPA Fine art Collection – Gallup NM". The Living New Bargain. Department of Geography, Academy of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 2015-07-19 .

- ^ Edward Alden Jewell (August 27, 1933). ""Musings Way Down east," New York Times"

- ^ "Bellis, Daisy Maud". Connecticut State Library. 27 August 1933. Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- ^ a b c d eastward f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v west x y z aa ab ac advert ae af ag ah ai aj ak al Cahill, Holger (1936). Barr, Alfred H. Jr. (ed.). New Horizons in American Art. New York: Museum of Modern Art. OCLC 501632161.

- ^ Abbott, Leala (December 2004). "Arts and Culture, Art Center records 1930–2004, Finding Aid". Milstein/Rosenthal Center for Media & Engineering science. 92nd Street Y. Archived from the original on 2015-06-21. Retrieved 2015-06-22 .

- ^ "Leon Bibel: Fine art, Activism, and the WPA". Lora Robins Gallery of Blueprint from Nature. University of Richmond. Archived from the original on 2015-06-23. Retrieved 2015-06-22 .

- ^ "Lucile Blanch, 1940 Oct. 31". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Establishment. Retrieved 2015-06-17 .

- ^ "1939 World's Fair Mural Study – Chicago IL". The Living New Deal. Department of Geography, University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 2015-06-ten .

- ^ a b c d "Williamsburg Housing Development Murals – Brooklyn NY". The Living New Deal. Department of Geography, Academy of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 2015-06-10 .

- ^ "Oral history interview with Adele Brandeis". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. June 1, 1965. Retrieved 2015-06-18 .

- ^ "Louise Brann, ca. 1935". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17 .

- ^ "Manuel Bromberg, 1939 Jan. 23". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17 .

- ^ "Oral history interview with James Brooks". Archives of American Fine art. Smithsonian Institution. June 10–12, 1965. Retrieved 2015-06-17 .

- ^ a b "Bailey, Chief Librarian, Praises WPA Art Project". Long Isle Sunday Printing. Long Island, New York. April 5, 1936.

- ^ "Selma Burke". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-16 .

- ^ "Letterio Calapai, ca. 1937". Athenaeum of American Fine art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17 .

- ^ "Oral history interview with Giorgio Cavallon, 1974". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2016-04-20 .

- ^ "P.S. 150 Mural – Queens NY". The Living New Deal. Department of Geography, University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 2016-05-11 .

- ^ "Dane Chanase, 1942 Jan. 26". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17 .

- ^ a b c d Mahoney, Eleanor (2012). "The Federal Fine art Project in Washington State". The Great Depression in Washington Country. Pacific Northwest Labor and Ceremonious Rights Project, University of Washington. Retrieved 2015-06-23 .

- ^ "Claude Clark Sr., In the Groove". The Collection Online. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2016-04-xx .

- ^ "Max Arthur Cohn". Smithsonian American Art Museum. Retrieved 2018-01-25 .

- ^ a b "Recovering America'south Fine art for America". Full general Services Administration. 2010. Archived from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2015-06-sixteen .

- ^ a b c d e f m h i j g l 1000 "Artists". WPA Art Inventory Project. Connecticut State Library. Archived from the original on 2015-07-04. Retrieved 2015-07-03 .

- ^ "Creative person: Alfred D. Crimi". The Living New Deal . Retrieved May 3, 2019.

- ^ "Francis Criss, 1940 Oct. 29". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17 .

- ^ "History and Mission". About United states of america. Phoenix Art Museum. Archived from the original on 2015-09-05. Retrieved 2015-06-22 .

- ^ Conn, Charis (February 15, 2013). "Fine art in Public: Stuart Davis on Abstract Fine art and the WPA, 1939". Annotations: The NEH Preservation Project. WNYC. Retrieved 2015-06-16 .

- ^ "Adolf Dehn, 1940 Oct. 29". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17 .

- ^ "Oral history interview with Burgoyne Diller". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Establishment. October two, 1964. Retrieved 2015-06-xvi .

- ^ "Isami Doi, Well-nigh Coney Island". The Collection Online. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2015-06-19 .

- ^ "Ruth Egri, 1937 Apr. 12". Archives of American Fine art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17 .

- ^ "Fritz Eichenberg, April". The Collection Online. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2015-06-22 .

- ^ "George Pearse Ennis, ca. 1936". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17 .

- ^ "Angna Enters, 1940 Nov. xviii". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Establishment. Retrieved 2015-06-17 .

- ^ "Louis Ferstadt, 1939 Jan. 25". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-nineteen .

- ^ "Alexander Finta, 1939 June 14". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17 .

- ^ "Federal Fine art Project, Photographic Division collection, circa 1920–1965, bulk 1935–1942". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-11-27 .

- ^ "Activist Arts". A New Deal for the Arts. National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved 2015-06-17 .

- ^ "Eugenie Gershoy, 1938 Mar. 28". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Establishment. Retrieved 2015-06-17 .

- ^ "Enrico Glicenstein, 1940 Sept. 29". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Establishment. Retrieved 2015-06-17 .

- ^ "Vincent Glinsky, 1939 Mar. 8". Archives of American Fine art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17 .

- ^ "Bertram Goodman, ca. 1939". Archives of American Fine art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17 .

- ^ "Marion Greenwood, 1940 June 4". Athenaeum of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17 .

- ^ "Waylande Gregory". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. June 2, 1937. Retrieved 2015-06-16 .

- ^ "Irving Guyer, Reading by Lamplight". The Collection Online. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2015-06-22 .

- ^ "Abraham Harriton, 1938 Aug. 16". Athenaeum of American Art. Smithsonian Establishment. Retrieved 2015-06-17 .

- ^ Megraw, Richard (January x, 2011). "Federal Art Project". KnowLA Encyclopedia of Louisiana. Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities. Archived from the original on September 15, 2015. Retrieved 2015-10-25 .

- ^ "Baronial Henkel, ca. 1939". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17 .

- ^ "Ralf C. Henricksen, 1938". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17 .

- ^ "Service on the home forepart At that place's a task for every Pennsylvanian in these civilian defense efforts". Library of Congress.

- ^ "Terminate and get your gratuitous fag bag Careless matches aid the Axis". Library of Congress.

- ^ "Donal Hord, 1937". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17 .

- ^ "Axel Horr [sic], 1940 June 28". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17 .

- ^ "Milton Horn, c. 1937". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17 .

- ^ "Eitaro Ishigaki, ca. 1940". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Establishment. Retrieved 2015-06-17 .

- ^ "Sargent Claude Johnson, Dorothy C.". The Collection Online. Metropolitan Museum of Fine art. Retrieved 2015-06-22 .

- ^ "Tom Loftin Johnson, 1938". Athenaeum of American Fine art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17 .

- ^ "William H. Johnson: A Guide for Teachers". American Art Museum and the Renwick Gallery. Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on 2015-06-13. Retrieved 2015-06-11 .

- ^ "Reuben Kadish, Conversation with a Quarry Master". The Collection Online. Metropolitan Museum of Fine art. Retrieved 2015-06-22 .

- ^ "Sheffield Kagy, Symphony Conductor". The Collection Online. Metropolitan Museum of Fine art. Retrieved 2015-06-22 .

- ^ "Jacob Kainen, Rooming Firm". The Collection Online. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2015-06-22 .

- ^ "David Karfunkle, ca. 1938". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Establishment. Retrieved 2015-06-19 .

- ^ "WPA - Works Progress Administration - New Bargain Artists | MOWA Online Archive". wisconsinart.org.

- ^ "Oral history interview with Lee Krasner". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. November 2, 1964 – Apr 11, 1968. Retrieved 2015-06-15 .

- ^ "Kalman Kubinyi, Skaters". The Collection Online. Metropolitan Museum of Fine art. Retrieved 2015-06-22 .

- ^ "Michael Lantz". Smithsonian American Fine art Museum. Retrieved 2015-06-nineteen .

- ^ "New Mexico State University: Branson Library Art – Las Cruces NM". The Living New Deal. Department of Geography, University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 2015-06-10 .

- ^ "Joseph LeBoit, Serenity". The Collection Online. Metropolitan Museum of Fine art. Retrieved 2015-06-19 .

- ^ "Monty Lewis, 1938 May 26". Athenaeum of American Fine art. Smithsonian Establishment. Retrieved 2015-06-17 .

- ^ "Elba Lightfoot, 1938 Jan. 14". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-xix .

- ^ "Murals Approved of 5 WPA Artists". The New York Times. October 28, 1935. Retrieved 2015-06-24 .

- ^ "Thomas Gaetano Lo Medico, 1938 May 12". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17 .

- ^ "Oral history interview with Guy and Genoi Pettit Maccoy". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Establishment. July 24, 1965. Retrieved 2015-06-13 .

- ^ "Federal Fine art Project Artists, 1937". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17 .

- ^ "Moissaye Marans, ca. 1939". Archives of American Fine art. Smithsonian Establishment. Retrieved 2015-06-17 .

- ^ "David Margolis, 1940 May 29". Archives of American Fine art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-xix .

- ^ "Jack Markow, Street in Manasquan". The Collection Online. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2015-06-22 .

- ^ "Mercedes Matter Interview Excerpts". Hans Hofmann: Artist/Teacher, Teacher/Artist. PBS. 2003. Retrieved 2015-06-fifteen .

- ^ "Dina Melicov, 1939 Apr. 26". Archives of American Fine art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17 .

- ^ "Hugh Mesibov". National Gallery of Art. National Gallery of Fine art. Retrieved 2021-02-xvi .

- ^ "Rex City High Schoolhouse Auditorium Bas Reliefs – Rex City CA". The Living New Deal. Section of Geography, Academy of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 2015-06-17 .

- ^ "Louise Nevelson". Guggenheim Collection Online. Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation. Retrieved 2015-06-15 .

- ^ "James Michael Newell, ca. 1937". Archives of American Fine art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17 .

- ^ "Elizabeth Olds, 1937". Athenaeum of American Art. Smithsonian Establishment. Retrieved 2015-06-18 .

- ^ Mary Ann Marger (1990-05-07). "Thinking in the Abstract Serial". Leningrad Times. St. Petersburg, Florida. p. 1D.

- ^ "William C. Palmer, 1936". Archives of American Fine art. Smithsonian Establishment. Retrieved 2015-06-17 .

- ^ "Irene Rice Pereira, 1938 Aug. 22". Archives of American Fine art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17 .

- ^ "Jackson Pollock". Guggenheim Drove Online. Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation. Archived from the original on 2015-05-30. Retrieved 2015-06-15 .

- ^ "Mac Raboy, Hitchhiker". The Collection Online. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2015-06-22 .

- ^ "Oral history interview with Ad Reinhardt". Athenaeum of American Art. Smithsonian Establishment. 1964. Retrieved 2015-06-16 .

- ^ "City Higher of San Francisco: Rivera Landscape – San Francisco CA". The Living New Deal. Department of Geography, Academy of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 2015-06-fifteen .

- ^ "Oral history interview with José de Rivera". Archives of American Fine art. Smithsonian Institution. February 24, 1968. Retrieved 2015-06-12 .

- ^ "Emanuel Glicen Romano, 1936 Nov. 23". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Establishment. Retrieved 2015-06-eighteen .

- ^ "Augusta Vicious". Smithsonian American Art Museum. Retrieved 2015-06-ten .

- ^ "The Harp past Augusta Barbarous". 1939 NY World'southward Fair. Archived from the original on 2017-03-12. Retrieved 2015-06-10 .

- ^ "Oral history interview with Louis Schanker". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Establishment. 1963. Retrieved 2015-06-eleven .

- ^ a b "Edwin & Mary Scheier". New Hampshire State Council on the Arts. February 12, 2015. Retrieved 2015-06-22 .

- ^ Pogrebin, Robin (September xvi, 2012). "At Harlem Hospital, Murals Get a New Life". The New York Times . Retrieved 2015-06-22 .

- ^ "Oral history interview with Ben Shahn". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Establishment. October iii, 1965. Retrieved 2015-06-13 .

- ^ "Rikers Island WPA Murals – East Elmhurst NY". The Living New Deal. Department of Geography, Academy of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 2015-06-10 .

- ^ "Oral history interview with Will Shuster, 1964". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2016-04-20 .

- ^ "Lane Tech College Prep High School Auditorium Mural – Chicago IL". The Living New Deal. Department of Geography, University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 2015-06-15 .

- ^ "Oral history interview with Joseph Solman". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-thirteen .

- ^ "Isaac Soyer, A Nickel a Smooth". The Drove Online. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2015-06-22 .

- ^ "George Washington High School: Stackpole Mural – San Francisco CA". The Living New Bargain. Department of Geography, Academy of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 2015-06-22 .

- ^ "Cesare Stea, 1939 Mar. 2". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Establishment. Retrieved 2015-06-17 .

- ^ "Sakari Suzuki, 1936 Dec. 2". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-14 .

- ^ Dunlap, David West. (November five, 2014). "At Futurity Cornell Campus, the Offset Step in Restoring Murals Is Finding Them". The New York Times . Retrieved 2015-06-22 .

- ^ "Timeline under Charles Umlauf bio on the UMLAUF Website".

- ^ "Jacques Van Aalten, 1938 May 26". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17 .

- ^ "Stuyvesant Van Veen papers, circa 1926-1988". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17 .

- ^ "Herman Roderick Volz, Lockout". The Collection Online. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2015-06-22 .

- ^ "Oral history interview with Mark Voris, 1965 February 11". www.aaa.si.edu.

- ^ "Murals by John Augustus Walker on permanent brandish in the Museum of Mobile vestibule, Mobile, Alabama". Library of Congress. Retrieved 2015-06-17 .

- ^ "Jean Xceron, 1942 Jan. 13". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-eighteen .

- ^ "Edgar L. Yaeger papers, 1923-1989". Archives of American Fine art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-17 .

- ^ "California Federal Art Project papers, 1935-1964". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-06-23 .

- ^ Nolte, Carl (February 27, 2015). "UCSF to permit public see trove of medical history murals". San Francisco Chronicle . Retrieved 2015-06-23 .

- ^ a b Parker, Thomas C. (Oct fifteen, 1938). "Federally Sponsored Community Fine art Centers". Bulletin of the American Library Association. American Library Clan. 32 (eleven): 807. Archived from the original on September 19, 2015. Retrieved 2015-ten-25 .

- ^ "Children cartoon at the Jacksonville Negro Art Heart of the WPA Federal Art Project- Jacksonville, Florida". Florida Memory. State Library and Archives of Florida. Retrieved 2015-ten-27 .

- ^ Rash, John (January 30, 2015). "The Walker's WPA roots are still relevant today". Star Tribune. Minneapolis, Minnesota. Retrieved 2015-06-21 .

- ^ Grieve, Victoria (2009). The Federal Art Project and the Cosmos of Middlebrow Culture. Urbana: Academy of Illinois Press. p. 145. ISBN9780252034213.

- ^ Abbott, Leala (December 2004). "Arts and Culture, Fine art Center records 1930–2004, Finding Aid". Milstein/Rosenthal Center for Media & Technology. 92nd Street Y. Archived from the original on 2015-06-21. Retrieved 2015-06-21 .

In 1935 and 1936, 92Y, in cooperation with the federal Works Progress Administration (Westward.P.A.) and the New York City Board of Education, began offering free courses … The Contemporary Art Middle, part of the W.P.A.'s Federal Art Projection, offered daytime courses for serious fine art students and was led by Nathaniel Dirk.

- ^ Mahoney, Eleanor (2012). "The Spokane Arts Eye: Bringing Art to the People". The Great Depression in Washington State. Pacific Northwest Labor and Civil Rights Project, University of Washington. Retrieved 2015-06-23 .

- ^ a b c d eastward f Cahill, Holger (1950). "Introduction". In Christensen, Erwin O. (ed.). The Index of American Design . New York: The Macmillan Company. pp. ix–xvii. OCLC 217678.

- ^ Herzberg, Max (October 15, 1950). "American Craftsmanship Offers Dazzler and Utility". Newark Evening News.

- ^ Jones, Louis C. (October 22, 1950). "Just Yesterday It Was Wooden Indians and Whittled Toys". The New York Times . Retrieved 2015-10-29 .

- ^ Jewell, Edward Alden (March xix, 1939). "Saving Our Usable Past". The New York Times . Retrieved 2015-10-29 .

- ^ "History". Index of American Blueprint. National Gallery of Fine art. Archived from the original on 2015-12-23. Retrieved 2015-10-28 .

- ^ Drawing on America'southward Past: Folk Art, Modernism, and the Index of American Design past Virginia Tuttle Clayton, Elizabeth Stillinger, Erika Doss, and Deborah Chotner. Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2002.

- ^ "Works Progress Assistants (WPA) Art Recovery Projection". Full general Services Administration. Archived from the original on September 19, 2015. Retrieved September 10, 2015.

- ^ a b "New Bargain Artwork: GSA'south Inventory Projection". General Services Administration. Retrieved 2015-06-13 .

- ^ "New Bargain Artwork: Ownership and Responsibleness". General Services Administration. Retrieved 2015-06-thirteen .

- ^ "Works Progress Administration (WPA) Art Recovery Project". Office of the Inspector General, General Services Administration. Archived from the original on 2015-09-xix. Retrieved 2015-06-xiii .

- ^ MacFarlane, Scott (September 17, 2014). "Lost History: Hunting for WPA Paintings". NBC 4. Washington, D.C. Retrieved 2015-06-13 .

- ^ MacFarlane, Scott (April twenty, 2015). "Dozens of Pieces of Lost WPA Fine art Found in California". NBC 4. Washington, D.C. Retrieved 2015-06-thirteen .

Further reading [edit]

- DeNoon, Christopher. Posters of the WPA (Los Angeles: Wheatley Press, 1987).

- Grieve, Victoria. The Federal Art Project and the Creation of Middlebrow Culture (2009) excerpt

- Kennedy, Roger Chiliad.; David Larkin (2009). When art worked. New York: Rizzoli. ISBN978-0-8478-3089-three.

- Kelly, Andrew, Kentucky by Design: American Civilization, the Decorative Arts and the Federal Art Project'south Alphabetize of American Pattern, Academy Press of Kentucky, 2015, ISBN 978-0-8131-5567-viii

- Russo, Jillian. "The Works Progress Administration Federal Fine art Project Reconsidered." Visual Resources 34.1-ii (2018): 13-32.

External links [edit]

- The Living New Deal inquiry project and online public annal at the Academy of California, Berkeley

- Recovering America'due south Art for America (2010), General Services Assistants curt documentary about efforts to recover WPA fine art

- Posters for the People, online annal of WPA posters

- WPA Posters collection at the Library of Congress

- New Deal Art Registry

- wpamurals.com – links to each state, with examples of WPA art in each

- Federal Art Projection Photographic Sectionalization drove at the Smithsonian Archives of American Fine art

- "1934: A New Bargain for Artists" Exhibition at the Smithsonian American Art Museum

- "Art Within Achieve": Federal Art Projection Customs Art Centers at George Mason University

- WPA Murals and American Abstract Artists at American Abstruse Artists

- WPA Prints and Murals in New York

- Collection: "Art of the Works Progress Assistants WPA" from the University of Michigan Museum of Fine art

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Federal_Art_Project

0 Response to "Regional Art Workshop Instructors in Illinois Wisconsin and Iowa"

Enregistrer un commentaire